In a post on VPT’s blog, I explain how rogue affiliates don’t just conceal their misconduct, but make it look like their traffic is coming from a totally unrelated site. Surprisingly simple tactics can even manipulate HTTP Referer headers — data that many analysts consider trustworthy since they are set by browsers rather than web sites directly. Fortunately, VPT automation catches, processes, and even tabulates these violations. Details: Traffic Laundering and Referer Faking.

Edge Shopping Stand-Down Violations

Affiliate network requirements require shopping plugins to “stand-down”—not present their affiliate links, not even highlight their buttons—when another publisher has already referred a user to a given merchant. Inexplicably, Microsoft Shopping often does no such thing.

The basic bargain of affiliate marketing is that a publisher presents a link to a user, who (the publisher hopes) clicks, browses, and buys. But if a publisher can put reminder software on a user’s computer or otherwise present messages within a user’s browser, it gets an extraordinary opportunity for its link to be clicked last, even if another publisher actually referred the user. To preserve balance and give regular publishers a fair shot, affiliate networks imposed a stand-down rule: If another publisher already referred the user, a publisher with software must not show its notification. This isn’t just an industry norm; it is embodied in contracts between publishers, networks, and merchants. (Terms and links below.)

In 2021, Microsoft added shopping features to its Edge web browser. If a user browses an ecommerce site participating in Microsoft Cashback, Edge Shopping open a notification, encouraging a user to click. Under affiliate network stand-down rules, this notification must not be shown if another publisher already referred that user to that merchant. Inexplicably, in dozens of tests over two months, I found the stand-down logic just isn’t working. Edge Shopping systematically ignores stand-down. It pops open. Time. After. Time.

This is a blatant violation of affiliate network rules. From a $3 trillion company, with ample developers, product managers, and lawyers to get it right. As to a product users didn’t even ask for. (Edge Shopping is preinstalled in Edge which is of course preinstalled in Windows.) Edge Shopping used to stand down when required, and that’s what I saw in testing several years ago. But later, something went terribly wrong. At best, a dev changed a setting and no one noticed. Even then, where are the testers? As a sometimes-fanboy (my first long-distance call was reporting a bug to Microsoft tech support!) and from 2018 to 2024 an employee (details below), I want better. The publishers whose commissions were taken—their earnings hang in the balance, and not only do they want better, they are suing to try to get it. (Again, more below.)

Contract provisions require stand-down

Above, I mentioned that stand-down rules are embodied in contract. I wrote up some of these contract terms in January (there, remarking on Honey violations from a much-watched video by MegaLag). Restating with a focus on what’s most relevant here (with emphasis added):

Commission Junction Publisher Service Agreement: “Software-based activity must honor the CJ Affiliate Software Publishers Policy requirements… including … (iv) requirements prohibiting usurpation of a Transaction that might otherwise result in a Payout to another Publisher… and (v) non-interference with competing advertiser/ publisher referrals.”

Rakuten Advertising Policies: “Software Publishers must recognize and Stand-down on publisher-driven traffic… ‘Stand-down’ means the software may not activate and redirect the end user to the advertiser site with their Supplier Affiliate link for the duration of the browser session. … The [software] must stand-down and not display any forms of sliders or pop-ups to prompt activation if another publisher has already referred an end user.” Stand down must be complete: In a stand-down situation, the publisher’s software “may not operate.”

Impact “Stand-Down Policy Explained”: Prohibits publishers “using browser extensions, toolbars, or in-cart solutions … from interfering with the shopping experience if another click has already been recorded from another partner.” These rules appear within an advertiser’s “Contracts” “General Terms”, affirming that they are contractual in nature. Impact’s Master Program Agreement is also on point, prohibiting any effort to “interfere with referrals of End Users by another Partner.”

Awin Publisher Code of Conduct: “Publishers only utilise browser extensions, adware and toolbars that meet applicable standards and must follow “stand-down” rules. … must recognise instances of activities by other Awin Publishers and “stand-down” if the user was referred to the Advertiser site by another Awin Publisher. By standing-down, the Publisher agrees that the browser extension, adware or toolbar will not display any form of overlays or pop-ups or attempt to overwrite the original affiliate tracking while on the Advertiser website.”

Edge does not stand-down

In test after test, I found that Edge Shopping does not stand-down.

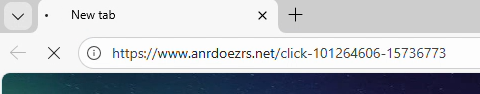

In a representative video, from testing on November 28, 2025, I requested the VPN and security site surfshark.com via a standard CJ affiliate link.

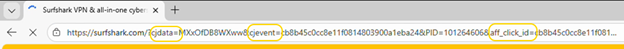

CJ redirected me to Surfshark with a URL referencing cjdata, cjevent, aff_click_id, utm_source=cj, and sf+cs=cj. Each of those parameters indicated that this was, yes, an affiliate redirect from CJ to Surfshark .

Then Microsoft Shopping popped up its large notification box with a blue button that, when clicked, invokes an affiliate link and sets affiliate cookies.

Notice the sequence: Begin at another publisher’s CJ affiliate link, merchant’s site loads, and Edge Shopping does not stand-down. This is squarely within the prohibition of CJ’s rules.

Edge sends detailed telemetry from browser to server reporting what it did, and to a large extent why. Here, Edge simultaneously reports the Surfshark URL (with cjdata=, cjevent=, aff_click_id=, utm_source=cj, and sf_cs=cj parameters each indicating a referral from CJ) (yellow) and also shouldStandDown set to 0 (denoting false/no, i.e. Edge deciding not to stand down) (green).

POST https://www.bing.com/api/shopping/v1/savings/clientRequests/handleRequest HTTP/1.1

...

{"anid":"","request_body":"{\"serviceName\":\"NotificationTriggering\",\"methodName\":\"SelectNotification\",\"requestBody\":\"{\\\"autoOpenData\\\":{\\\"extractedData\\\":{\\\"paneState\\\":{\\\"copilotVisible\\\":false,\\\"shoppingVisible\\\":false}},\\\"localData\\\":{\\\"isRebatesEnabled\\\":true,\\\"isEdgeProfileRebatesUser\\\":true,\\\"shouldStandDown\\\":0,\\\"lastShownData\\\":null,\\\"domainLevelCooldownData\\\":[],\\\"currentUrl\\\":\\\"https://surfshark.com/?cjdata=MXxOfDB8WXww&cjevent=cb8b45c0cc8e11f0814803900a1eba24&PID=101264606&aff_click_id=cb8b45c0cc8e11f0814803900a1eba24&utm_source=cj&utm_medium=6831850&sf_cs=cj&sf_cm=6831850\\\" ...

With a standard CJ affiliate link, and with multiple references to “cj” right in the URL, I struggle to see why Edge failed to realize this is another affiliate’s referral. If I were writing stand-down code, I would first watch for affiliate links (as in the first screenshot above), but surely I’d also check the landing page URL for significant strings such as source=cj. Both methods would have called for standing down.

Another notable detail in Edge’s telemetry is that by collecting the exact Surfshark landing page URL, including the PID= parameter (blue), Microsoft receives information about which other publisher’s commission it is taking. Were litigation to require Microsoft to pay damages to the publishers whose commissions it took, these records would give direct evidence about who and how much, without needing to consult affiliate network logs. This method doesn’t always work—some advertisers track affiliates only through cookies, not URL parameters; others redirect away the URL parameters in a fraction of a second. But when it works, more than half the time in my experience, it’s delightfully straightforward.

Additional observations

If I observed this problem only once, I might ignore it as an outlier. But no. Over the past three weeks, I tested a dozen-plus mainstream merchants from CJ, Rakuten Advertising, Impact, and Awin, in 25+ test sessions, all with screen recording. In each test, I began by pasting another publisher’s affiliate link into the Edge address bar. Time after time, Edge Shopping did not stand-down, and presented its offer despite the other affiliate link. Usually Edge Shopping’s offer appeared in a popup as shown above. The main variation was whether this popup appeared immediately upon my arrival at the merchant’s home page (as in the Surfshark example above), versus when I reached the shopping cart (as in the Newegg example below)s.

In a minority of instances, Edge Shopping presented its icon in Edge’s Address Bar rather than opening a popup. While this is less intrusive than a popup, it still violates the contract provisions (“non-interference”, “may not activate”, “may not operate”, may not “interfere”, all as quoted above). Turning blue to attract a user’s attention—this invites a user to open Edge Shopping and click its link, causing Microsoft to claim commission that would otherwise flow to another publisher. That’s exactly what “non-interference” rules out. “May not operate” means do nothing, not even change appear in the Address Bar. Sidenote: At Awin, uniquely, this seems to be allowed. See Publisher Code of Conduct, Rule 4, guidance 4.2. For Awin merchants, I count a violation only if Edge Shopping auto-opened its popup, not if it merely appeared in the Address Bar.

Historically, some stand-down violations were attributed to tricky redirects. A publisher might create a redirect link like https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/out/link/53437/186063/4/153497/?merchant=Lego which redirects (directly or via additional steps) to an affiliate link and on to the merchant (in this case, Lego). Historically, some shopping plugins had trouble recognizing an affiliate link when it occurred in the middle of a redirect chain. This was a genuine concern when first raised twenty-plus years ago (!), when Internet Explorer 6’s API limited how shopping plugins could monitor browser navigation. Two decades of improvements in browser and plugin architecture, this problem is in the past. (Plus, for better or worse, the contracts require shopping plugins to get it right—no matter the supposed difficulty.) Nonetheless, I didn’t want redirects to complicate interpretation of my findings. So all my tests used the simplest possible approach: Navigate directly to an affiliate link, as shown above. With redirects ruled out, the conclusion is straightforward: Edge Shopping ignores stand-down even in the most basic conditions.

I mentioned above that I have dozens of examples. Posting many feels excessive. But here’s a second, as to Newegg, from testing on December 5, 2025.

Litigation ongoing

Edge’s stand-down violations are particularly important because publishers have pending litigation about Edge claiming commissions that should have flowed to them. After MegaLag’s famous December 2024 video, publishers filed class action litigation against Honey, Capital One, and Microsoft. (Links open the respective dockets.)

I have no role in the case against Microsoft and haven’t been in touch with plaintiffs or their lawyers. If I had been involved, I might have written the complaint and Opposition to Motion to Dismiss differently. I would certainly have used the term “stand-down” and would have emphasized the governing contracts—facts for some reason missing from plaintiffs’ complaint.

Microsoft’s Motion to Dismiss was fully briefed as of September 2, and the court is likely to issue its decision soon.

Microsoft’s briefing emphasizes that it was the last click in each scenario plaintiffs describe, and claims that last click makes it “entitled to the purchase attribution under last-click attribution.” Microsoft ignores the stand-down requirements laid out above. Had Microsoft honored stand-down, it would have opened no popup and presented no affiliate link—so the corresponding publisher would have been the last click, and commission would have flowed as plaintiffs say it should have.

Microsoft then remarks on plaintiffs not showing a “causal chain” from Microsoft Shopping to plaintiffs losing commission, and criticizes plaintiffs’ causal analysis as “too weak.” Microsoft emphasizes the many uncertainties: customers might not purchase, other shopping plug-ins might take credit, networks might reallocate commission for some other reason. Here too, Microsoft misses the mark. Of course the world is complicated, and nothing is guaranteed. But Microsoft needed only to do what the contracts require: stand-down when another publisher already referred that user in that shopping session.

Later, Microsoft argues that its conduct cannot be tortious interference because plaintiffs did not identify what makes Microsoft’s conduct “improper.” Let me leave no doubt. As a publisher participating in affiliate networks, Microsoft was bound by networks’ contracts including the stand-down terms quoted above. Microsoft dishonored those contracts to its benefit and to publishers’ detriment, contrary to the exact purpose of those provisions and contrary to their plain language. That is the “improper” behavior which plaintiffs complain about. In a puzzling twist, Microsoft then argues that it couldn’t “reasonably know[]” about the contracts of affiliate marketing. But Microsoft didn’t need to know anything difficult or obscure; it just needed to do what it had, through contract, already promised.

Microsoft continues: “In each of Plaintiffs’ examples, a consumer must affirmatively activate Microsoft Shopping and complete a purchase for Microsoft to receive a commission, making Microsoft the rightful commission recipient if it is the last click in that consumer’s purchase journey.” It is as if Microsoft’s lawyers have never heard of stand-down. There is nothing “rightful” about Microsoft collecting a commission by presenting its affiliate link in situations prohibited by the governing contracts.

Microsoft might or might not be right that its conduct is acceptable in the abstract. But the governing contracts plainly rule out Microsoft’s tactics. In due course maybe plaintiffs will file an amended complaint, and perhaps that will take an approach closer to what I envision. In any event, whatever the complaint, Microsoft’s motion to dismiss arguments seem to me plainly wrong because Microsoft was required by contract to stand-down—and it provably did not.

***

In June 2025, news coverage remarked on Microsoft removing the coupons feature from Edge (a different shopping feature that recommended discount codes to use at checkout) and hypothesized that this removal was a response to ongoing litigation. But if Microsoft wanted to reduce its litigation exposure, removing the coupons feature wasn’t the answer. The basis of litigation isn’t that Microsoft Shopping offers (offered) coupons to users. The problem is that Microsoft Shopping presents its affiliate link when applicable contracts say it must not.

Catching affiliate abuse

I’ve been testing affiliate abuse since 2004. From 2004 to 2018, I ran an affiliate fraud consultancy, which caught all manner of abuse—including shopping plugins (what that page calls “loyalty programs”), adware, and cookie-stuffing. My work in that period included detecting the activity that led to the 2008 litigation civil and criminal charges against Brian Dunning and Shawn Hogan (a fact I can only reveal because an FBI agent’s declaration credited me). I paused this work from 2018 to 2024, but resumed it this year as Chief Scientist of Visible Performance Technologies, which provides automation to detect stand-down violations, adware, low-intention traffic, and related abuses. As you’d expect, VPT has long been reporting Edge stand-down violations to clients that contract for monitoring of shopping plugins.

My time from 2018 to 2024, as an employee of Microsoft, is relevant context. I proposed Bing Cashback and led its product management and business development through launch. Bing Cashback put affiliate links into Bing search results, letting users earn rebates without resorting to shopping plugins or reminders, and avoiding the policy complexities and contractual restrictions on affiliate software. Meanwhile, Bing Cashback provided a genuine reason for users to choose Bing over Google. Several years later, others added cashback to Edge, but I wasn’t involved in that. Later I helped improve the coupons feature in Edge Shopping. In this period, I never saw Edge Shopping violate stand-down rules.

I ended work with Bing and Edge in 2022, after which I pursued AI projects until I resigned in 2024. I don’t have inside knowledge about Edge Shopping stand-down or other aspects of Microsoft Cashback in Edge. If I had such information, I would not be able to share it. Fortunately the testing above requires no special information, and anyone with Edge and a screen-recorder can reproduce what I report.

SEC Complaint about AppLovin Nonconsensual Installs

See important disclosures including my related financial interests.

In response to my report of AppLovin installing apps onto users’ devices without consent, Bloomberg published AppLovin Axes Product Tied to Unwanted App Download Allegations.

I filed a complaint with the SEC about what I claim to be material false statements in AppLovin’s remarks to Bloomberg and elsewhere. Here:

The complaint has three parts. First, as to the nonconsensual installations. I proved AppLovin is installing without user consent. But AppLovin’s CEO wrote in February “Every download results from an explicit user choice.” And AppLovin told Bloomberg today: “Users never get downloads with any of our products without explicitly requesting it.” Both false. The difference is fundamental. If users actually agree to the installations, great, go ahead. But if, as I say I amply proved, the installations are without user consent, then they are way out of line — outside user expectations, contrary to Google’s security architecture for Android, maybe proper basis for litigation.

How could AppLovin be planning to argue that its installations entail “consent”? Their best argument — not a very good one — is that users at least tapped ads, and that showed some level of interest. Two reactions to that. One, that’s not what users reasonably expect. An ad tap is not an agreement to install. On Android, installations require pressing the big blue Install button at Google Play Store, not just a random tap. Two, AppLovin’s design makes inadvertent ad taps particularly likely. Most ads have a long delay, then show a small arrow in one corner, which, when tapped, brings a user to a second screen, with a further delay, and then finally an X elsewhere. If you’ve never had the pleasure of seeing this ad format, count yourself lucky. It is beyond annoying! The two waits, and the arrow and X in different corners, make it especially easy to tap accidentally. Ultimately, tapping an ad just is not consent to install. Whatever contortions AppLovin’s lawyers and publicists may attempt, users with the slimmest tech experience know the difference

Second, AppLovin today told Bloomberg not just that it had discontinued the Array installation business, and that it did so because that offering “was not economically viable for us.” But for seven adjacent quarters (latest in August 2025), AppLovin’s SEC filings touted Array as a source of “future growth.” AppLovin’s CFO in February 2024 cited Array installations for “contributions” to growth. I say the real reason AppLovin turned off Array isn’t because it’s unprofitable. It’s because they got caught.

Third, AppLovin told Bloomberg the Array installations were only a “test.” But Array was available as early as 2023. Jia-Hong Xu, previously Head of Product for Array, wrote on his LinkedIn page that he led this product beginning in July 2023. My tabulation of user complaints shows users reporting problems reasonably attributed to AppLovin as early as August 2023. Reinhold Kesler checked historic AppBrain crawls and found that as of December 2022, 37 apps already had manifest entries that allowed AppLovin’s nonconsensual installs. A maxim remarks “always be testing”, and that much I agree with. On some level every decision is a test, always up for reevaluation. But in calling Array a test, AppLovin wants to claim this is small. That claim should be supported with real evidence — exactly how many installs, starting on what date, ending on what date, and with what permission? The one-word label “test” won’t suffice.

***

Publicly-traded firms owe their investors forthright statements about material information. I say AppLovin fell short, in fact was materially misleading in the statements both in February (on its web site) and today (to Bloomberg). I look forward to the SEC investigating.

Note: The federal government is currently partially shut down. But the SEC site proclaims: “The SEC has staff available to respond to emergency situations with a focus on the market integrity and investor protection components of our mission.” My complaint is within that mandate.

Updated October 17 to add Kesler’s finding as to 2022 status and duration of the “test”

AppLovin Nonconsensual Installs

See important disclosures including my related financial interests.

Mobile adtech juggernaut AppLovin recently faced multiple allegations of misconduct. Allegations run the gamut—privacy, ad targeting, even national security and ties to China. I was among the researchers consulted by skeptical investors this spring, and I was quoted in one of their reports, explaining my concerns about AppLovin installing other games without user consent.

Today I argue that AppLovin places apps on users’ Android devices without their consent. As a maxim says, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, but I embrace that high bar. First, I study AppLovin source code and find that it installs other apps without users being asked to consent. I use a decompiler to access Java source for AppLovin’s SDK and middleware, plus partners’ install helpers—following the execution path from an ad tap (just clicking an ad, potentially a misclick aiming for a tiny X button, with no Install button even visible on screen) through to an installation. AppLovin used an obfuscator to conceal most function names and variable names, so the Java code is no easy read. But with patience, suitable devs can follow the logic. Usefully, some key steps are in JavaScript—again obfuscated (minified), but readable thanks to a pretty-printer. I except the relevant parts and explain line by line.

Second, I gather 208 complaints that all say basically the same thing: users are receiving apps in situations where (at a minimum) they don’t think they agreed. The details of these complaints match what the code indicates: Install helpers (including from Samsung and T-Mobile) perform installs at AppLovin’s direction, causing most users to blame the install helpers (despite their generic names like Content Manager, Device Manager, and AppSelector). Meanwhile, most complaints report no notification or request for approval prior to install, but others say they got a screen which installed even when they pressed X to decline, and a few report a countdown timer followed by automatic installation. Beyond prose complaints, a handful of complaints include screenshots, and one has a video. Wording from the screenshots and video match strings in the code, and users’ reports of auto-installs, X’s, and countdowns similarly match three forks in AppLovin’s code. Overall, users are furious, finding these installations contrary to both Android security rules and widely-held expectations.

AppLovin CEO Adam Foroughi posted in February 2025 that “Every download results from an explicit user choice—whether via the App Store or our Direct Download experience.” AppLovin Array Privacy Policy similarly claims that AppLovin “facilitates the on-device installation of mobile apps that you choose to download.” But did users truly make an “explicit … choice” and “choose to download” these apps? Complaints indicate that users don’t think they chose to install. And however AppLovin defends its five-second countdowns, a user’s failure to reject a countdown certainly is not an “explicit” choice to install. Nor is “InstallOnClose” (a quote from AppLovin’s JavaScript) consistent with widely-held expectations that “X” means no. Perhaps Foroughi intends to argue that a user “consents” to install any time the user taps an ad, but even that is a tall order. One, AppLovin’s X’s are unusually tiny, so mis-taps are especially likely. Two, users expect an actual Install button (not to mention appropriate contract formalities) before an installation occurs; users know that on Android, an arbitrary tap cannot ordinarily install an app. Ultimately, “explicit user choice” is a high bar, and user complaints show AppLovin is nowhere close.

The role of manufacturers and carriers

Why would Samsung, T-Mobile, and others grant AppLovin the ability to install apps? Two possibilities:

- Financial incentives. AppLovin pays manufacturers and carriers for the permissions it seeks. These elevated permissions may be unusual, and the resulting installations are predictably annoying and unwanted for users. But at the right price, some partners may agree.

- Scope creep. Public statements indicate manufacturers and carriers authorized AppLovin to perform “out-of-box experience” (OOBE) installs—recommending and installing apps during initial device setup. Install helpers were designed to support this narrow context. But my review of install helper code shows no checks to limit installations to the OOBE window. A simple safeguard—such as rejecting installs more than two hours after first boot—would prevent ongoing installs. By omitting such safeguards, manufacturers and carriers effectively granted AppLovin open-ended install rights, whether or not that was their intent.

So far manufacturers and carriers haven’t said whether they approve what AppLovin is doing. Journalist Mike Shields asked Samsung, but they declined to comment. Perhaps my article will prompt them to take another look.

Sources of evidence

Five overlapping categories of evidence offer a mutually-reinforcing picture of nonconsensual installations:

- Execution path. Source code extracted from test devices shows how an ad tap leads all the way to an installation, without a user pressing “Install” or similar at a consent screen.

- Labels and strings. Code snippets reference installation without a user request or consent.

- Permissions. App manifests include nonstandard entries consistent with apps asking AppLovin middleware to install other apps.

- User complaints. 208 distinct complaints describe apps being installed while playing games or viewing ads. A few complaints include relevant screenshots and even video of nonconsensual installations. Complaints, screenshots, and videos match unusual details visible in the code.

- AppLovin statements. Public statements use euphemistic or contradictory language about user “choice” and “direct downloads,” suggesting attempts to obscure nonconsensual installs.

I also examine the legal and financial risks associated with nonconsensual installations.

Interpreting AppLovin statements to the public about user “choice” to install

This post is part of AppLovin Nonconsensual Installs. See important disclosures.

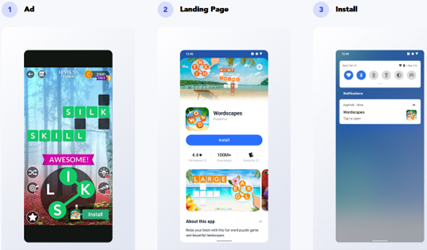

AppLovin’s “Array” page (now removed, but see Archive.org preserved copy) describes “seamless installs” in which “users choose whether to install.” The page depicts a three-step installation sequence: (1) AppLovin presents an ad, (2) AppLovin presents a landing page with an oversized bold blue “Install” button, and (3) installation is complete.

But AppLovin’s page never promises that this three-step process is always used. In fact, it labels the screenshots as an “example,” leaving open the possibility that some installations proceed differently. Could AppLovin sometimes skip the landing page (Step 2)? If so, the process would lack any moment where the user presses “Install” or otherwise agrees to install.

Other AppLovin materials suggest this must happen. For example, AppLovin AppHub JavaScript settings refer to “Download apps with a single click.” Since clicking an ad is already one click, a second click on “Install” would make two clicks—not one. This suggests that in at least some cases, Step 2 is omitted, as confirmed by my code review, which points to an “AutoInstall” path.

Meanwhile, AppLovin makes strong claims that users “choose” to install apps:

- A February 26, 2025 post from AppLovin CEO Adam Foroughi: “Every download results from an explicit user choice—whether via the App Store or our Direct Download experience.”

- AppLovin Array Privacy Policy (archived copy): “Direct Download … facilitates the on-device installation of mobile apps that you choose to download.”

- AppLovin Array Terms states that “Direct Download … facilitates the on-device installation of mobile apps that you choose download” and “You decide whether to download and install an application…”

How do we reconcile these statements with the “single-click” option, the “AutoInstall” code, and widespread user complaints? The most plausible interpretation is that AppLovin treats a tap on an ad itself as the user’s “choice” to install—even if the user never presses an Install button. Most users would disagree: ordinarily, tapping an ad only opens Google Play, where a further click is required. And because AppLovin’s “x” buttons are small and tucked in the corner, mistaken taps are especially likely.

If we accept AppLovin interpretation of a single ad tap as a user’s authorization to install, then Foroughi’s statement and the Privacy Policy might be literally true, but still highly misleading.

Contradictory statements about the size of the Direct Download business

The Financial Times reports that Applovin says “direct download business was never a major growth revenue driver”:

AppLovin also had a call with sell-side stock analysts on Wednesday, according to a note from Bank of America. In that call, the CEO assured analysts that the direct-download business was “never a major growth revenue driver,” the analysts wrote. They summarised his comments as saying “AppLovin’s [direct download] revenues are de minimis”.

BofA analyst Omar Dessouky told Alphaville that the direct-download business are distinct and totally separate from in-game downloads, and that competitors Digital Turbine and Unity have a big head-start on that business. As for the App Store policies, there seem to be enough complaints about other companies doing it that the practice isn’t being censured (this one, for example, seems to be about Digital Turbine).

These claims are difficult to reconcile with remarks from ex-employee Jia-Hong Xu, previously Head of Product for AppLovin Array, who wrote on LinkedIn that Direct Download is AppLovin’s “top revenue driver”:

Xu later deleted that remark. But on his own initiative, or under pressure from AppLovin (after investor Culper Research highlighted the claim in a February 2025 report)?

AppLovin: Server-side kill switch — automatic installations occur only if a token is provided

This post is part of AppLovin Nonconsensual Installs. See important disclosures.

It is by no means assured that AppLovin will perform an automatic installation of an app featured in a given ad. For one, the Apphub/Array package must be present and functional, and must have an install partner. Without these, there can be no automatic installation. Some phones (including Google Pixels) never have install helpers. High-end phones and unlocked phones are less likely to have install helpers.

Furthermore, the SDK startDirectInstallOrDownloadProcess() code indicates that direct downloads occur only if AppLovin servers send a “download token” to the app/SDK to authorize a direct download. See startDirectInstallOrDownloadProcess():

public void startDirectInstallOrDownloadProcess(ArrayDirectDownloadAd arrayDirectDownloadAd, Bundle bundle, DirectDownloadListener directDownloadListener) {

if (this.appHubService == null) {

if (C1886x.m8960Fn()) {

this.logger.m8974i(TAG, "Cannot begin Direct Install / Download process - service disconnected");

}

directDownloadListener.onFailure();

return;

}

if (!arrayDirectDownloadAd.isDirectDownloadEnabled()) {

if (C1886x.m8960Fn()) {

this.logger.m8974i(TAG, "Cannot begin Direct Install / Download process - missing token");

}

directDownloadListener.onFailure();

return;

}

try {

...

The underlying isDirectDownloadEnabled():

public boolean isDirectDownloadEnabled() {

return StringUtils.isValidString(getDirectDownloadToken());

}

The token is retrieved from within the ad object (i.e. delivered at runtime along with ad creative):

public String getDirectDownloadToken() {

return getStringFromAdObject("ah_dd_token", null);

}

protected String getStringFromAdObject(String str, String str2) {

String string;

synchronized (this.adObjectLock) {

string = JsonUtils.getString(this.adObject, str, str2);

}

return string;

}

It turns out “isValid” just means nonempty:

public static boolean isValidString(String str) {

return !TextUtils.isEmpty(str);

}

This is an unusual approach to token-based installations – neither a cryptographic verification nor a check for user consent. Instead, AppLovin can proceed with an automatic installation, or not, based merely on a string in the ad object being nonempty. The apparent benefit to AppLovin is that it can condition a direct download on any information known to the server as it sends the ad object. For example, AppLovin can limit direct downloads by IP address and geography, such as never targeting countries or regions deemed high-risk. (AppLovin can geofence jurisdictions where consumer protection authorities take a particularly dim view of nonconsensual installations. AppLovin can geofence the headquarters of companies that it doesn’t want to see nonconsensual installations.) AppLovin can equally avoid users with certain profiles, such as users who have seen less than x ads (who might be security researchers rather than serious gamers). Finally, this architecture allows AppLovin to end all direct downloads on a moment’s notice — as it might anticipate needing to do if facing public criticism.

AppLovin Execution Path: T-Mobile InstallerHelper performs an install

This post is part of AppLovin Nonconsensual Installs > Execution Path. See important disclosures.

T-Mobile’s InstallerHelper sends execution to the separate APK com.tmobile.dm.cm:

public final InstallerHelperResult startInstall(String absPath, String packageName, boolean shortcut, int requestedScreen, int colX, int rowY, String triggerType, String className, String action, String extraData, String receiverPermission) throws RemoteException {

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(absPath, "absPath");

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(packageName, "packageName");

if (!isReady()) {

if (this.f19986b) {

Log.e("CM_TMO_SDK", "Cannot start, service not ready");

}

return new InstallerHelperResult.Fail(ConstantsKt.ERROR_KEY_NOT_BOUND, null);

}

...

Message messageObtain = Message.obtain();

messageObtain.what = 100;

messageObtain.replyTo = this.f19993i;

File file = new File(absPath);

Bundle bundle = new Bundle();

bundle.putString(EXTRA_LOCATION, Uri.fromFile(file).toString());

bundle.putString(EXTRA_PACKAGE, packageName);

bundle.putString("com.tmobile.dm.cm.extra.PACKAGE_NAME", this.f19985a.getPackageName());

bundle.putBoolean(EXTRA_SHORTCUT, shortcut);

...

messageObtain.setData(bundle);

try {

Messenger messenger = this.f19992h;

if (messenger != null) {

messenger.send(messageObtain);

}

return new InstallerHelperResult.Success(ConstantsKt.SUCCESS_KEY);

According to the InstallerHelper class definition, the constant messageObtain.what=100 denotes performing an installation:

public static final int REQUEST_INSTALL = 100;

T-Mobile’s com.tmobile.dm.cm has special permissions including the permission to install apps. Its manifest declares these permissions:

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.INSTALL_PACKAGES"/>

T-Mobile’s message dispatcher m14262a() receives the request from InstallerHelper, classifies the message based on message.what message type, and routes the message accordingly:

public final void m14262a(Message message) { //message dispatcher

...

int i8 = message.what;

...

switch (i8) {

case 100:

companion.mo19362i("doHandleMsg(): Install requested: %s", 100);

synchronized (this.f33457b) {

size3 = this.f33457b.size();

}

Bundle data3 = message.getData();

String m14260j = m14260j(data3.getString(AppConstants.EXTRA_REQUESTER_PACKAGE), data3.getStringArray(AppConstants.EXTRA_SERVICE_REQUESTER_PACKAGE));

String string = data3.getString("location");

String string2 = data3.getString(AppConstants.EXTRA_PACKAGE);

int i9 = data3.getInt(AppConstants.EXTRA_UID, 0);

boolean z7 = data3.getBoolean(AppConstants.EXTRA_SIGNED, true);

Intrinsics.checkNotNull(messenger);

LocalInstallHandlerParams localInstallHandlerParams = new LocalInstallHandlerParams(messenger, string, string2, i9, z7, m14260j);

localInstallHandlerParams.setAddShortcut(data3.getBoolean(AppConstants.EXTRA_SHORTCUT, false));

localInstallHandlerParams.setRequestedScreen(data3.getInt(AppConstants.EXTRA_REQUEST_SCREEN, 0));

localInstallHandlerParams.setColX(data3.getInt(AppConstants.EXTRA_COLX, 0));

localInstallHandlerParams.setRowY(data3.getInt(AppConstants.EXTRA_ROWY, 0));

localInstallHandlerParams.setTriggerType(data3.getString(AppConstants.EXTRA_TRIGGER_TYPE));

localInstallHandlerParams.setClassName(data3.getString(AppConstants.EXTRA_CLASS_NAME));

localInstallHandlerParams.setAction(data3.getString("action"));

localInstallHandlerParams.setExtraData(data3.getString(AppConstants.EXTRA_DATA));

localInstallHandlerParams.setReceiverPermission(data3.getString(AppConstants.EXTRA_BROADCAST_PERMISSION));

synchronized (this.f33457b) {

this.f33457b.add(size3, localInstallHandlerParams);

}

if (size3 == 0 && this.f33458c == null) {

this.f33460e.sendEmptyMessage(102);

return;

}

...

The sendEmptyMessage(102) method sends execution to m14262a case 102, which again calls startInstall(), this time with case 102:

case 102:

companion.mo19362i("doHandleMsg(): Processing install: %s", 102);

synchronized (this.f33457b) {

size4 = this.f33457b.size();

}

if (size4 > 0) {

synchronized (this.f33457b) {

handlerParams = (HandlerParams) this.f33457b.remove(0);

this.f33458c = handlerParams;

}

if (handlerParams != null) {

if (handlerParams instanceof ModifyParams) {

((ModifyParams) handlerParams).startModify(this);

return;

} else if (handlerParams instanceof UninstallParams) {

((UninstallParams) handlerParams).startUninstall(this);

return;

} else {

handlerParams.startInstall(this);

return;

}

}

return;

}

return;

Next handlerParams.startInstall() calls prepareInstall(), which in turn calls performInstallBundle():

public boolean startInstall(@NotNull ServiceHandler handler) {

Intrinsics.checkNotNullParameter(handler, "handler");

int prepareInstall = prepareInstall(handler);

...

public int prepareInstall(@NotNull ServiceHandler handler) {

...

return performInstallBundle(handler.getMContext());

}

Then performInstallBundle() passes execution to InstallParams method m14247a():

public final int performInstallBundle(@NotNull Context context) {

…

int m14247a = m14247a(context, "", arrayList, false);

Finally, m14247a tells the Android Package Manager to perform the install:

//pass install to Android Package Manager

public final int m14247a(Context context, String str, ArrayList arrayList, boolean z6) throws Throwable {

PackageInstaller packageInstaller = context.getPackageManager().getPackageInstaller();

...

PackageInstaller.SessionParams sessionParams = new PackageInstaller.SessionParams(this.mInstallSessionMode);

sessionParams.setAppLabel(getAppName(context));

sessionParams.setAppPackageName(getCom.google.firebase.remoteconfig.RemoteConfigConstants.RequestFieldKey.PACKAGE_NAME java.lang.String());

...

setMInstallerSessionId$app_currentRelease(packageInstaller.createSession(sessionParams));

...

this.f33245C = packageInstaller.openSession(getMInstallerSessionId());

Iterator it = arrayList.iterator();

Intrinsics.checkNotNullExpressionValue(it, "iterator(...)");

int iM14248c2 = -999;

while (it.hasNext()) {

Object next = it.next();

Intrinsics.checkNotNullExpressionValue(next, "next(...)");

Timber.INSTANCE.getClass();

iM14248c2 = m14248c((String) next);

if (1 != iM14248c2) {

break;

}

}

...

Intent intent = new Intent(context, (Class<?>) InternalReceiver.class);

intent.setAction(InternalReceiver.ACTION_INSTALLER_RESULT);

PendingIntent broadcast = PendingIntent.getBroadcast(context, 0, intent, Build.VERSION.SDK_INT >= 31 ? 167772160 : 134217728);

PackageInstaller.Session session = this.f33245C;

if (session != null) {

session.commit(broadcast.getIntentSender());

}

AppHub uses a variety of installers with heightened privileges from manufacturer or carrier

The preceding section discusses AppHub passing execution to T-Mobile InstallerHelper. But consider devices that don’t have T-Mobile InstallerHelper. AppHub code shows AppLovin also using other install helpers from other manufacturers and carriers.

T-Mobile and Sprint

public final InstallerHelperResult bindToInstaller(boolean useForegroundServiceIfNeeded) {

...

PackageManager.PackageInfoFlags of;

PackageManager.PackageInfoFlags of2;

PackageManager.ResolveInfoFlags of3;

if (isReady()) {

if (this.f19986b) {

Log.e("CM_TMO_SDK", "Binding failed, service already bound");

}

return new InstallerHelperResult.Fail(ConstantsKt.ERROR_KEY_ALREADY_BOUND, null);

}

if (((Number) this.f19989e.getValue()).intValue() < 3000) {

return new InstallerHelperResult.Fail(ConstantsKt.ERROR_KEY_VERSION_NOT_SUPPORTED, null);

}

String str = "com.tmobile.dm.cm.extra.PACKAGE_NAME";

String str2 = "com.tmobile.dm.cm.extra.APP_LABEL";

if (AbstractC0945q.m2146P((String) this.f19987c.getValue(), "com.tmobile.dm.cm.permission.UPDATES_INSTALL", false)) {

intent = new Intent("com.tmobile.action.INSTALLER_SERVICE");

} else if (AbstractC0945q.m2146P((String) this.f19987c.getValue(), "com.tmobile.dm.cm.permission.TRUSTED_UPDATES_INSTALL", false)) {

intent = new Intent("com.tmobile.action.INSTALLER_TRUSTED_SERVICE");

} else {

str = "com.sprint.ce.updater.extra.PACKAGE_NAME";

str2 = "com.sprint.ce.updater.extra.APP_LABEL";

if (AbstractC0945q.m2146P((String) this.f19987c.getValue(), "com.sprint.permission.INSTALL_UPDATES", false)) {

intent = new Intent("com.sprint.action.INSTALLER_SERVICE");

} else {

if (!AbstractC0945q.m2146P((String) this.f19987c.getValue(), "com.sprint.ce.updater.permission.TRUSTED_INSTALL_UPDATES", false)) {

return new InstallerHelperResult.Fail(ConstantsKt.ERROR_KEY_PERMISSION_SECURITY_ISSUE, null);

}

intent = new Intent("com.sprint.action.INSTALLER_TRUSTED_SERVICE");

...

Samsung

public class SamsungBindInstallAgentService extends Hilt_SamsungBindInstallAgentService {

public static final String ACTION_INSTALL_PACKAGE_BY_SAMSUNG = "action_install_package_by_samsung";

private static final String INSTALL_AGENT_CLASS = "com.sec.android.app.samsungapps.api.InstallAgent";

private static final String INSTALL_AGENT_PACKAGE = "com.sec.android.app.samsungapps";

public static final String PARAM_DOWNLOAD_PACKAGE = "param_download_package";

ActiveDeliveryTrackerManager activeDeliveryTrackerManager;

AppDeliveryInfoDao appDeliveryInfoDao;

Executor deliveryCoordinatorExecutor;

private InterfaceC1402c installAgentAPI;

Logger logger;

SamsungErrorCodeManager samsungErrorCodeManager;

private final IBinder binder = new LocalBinder();

volatile boolean mBound = false;

volatile boolean isBinding = false;

IBinder samsungInstallerBinder = null;

String activeTargetPackageName = null;

private volatile ArrayDeque installTaskQueue = new ArrayDeque<>();

private ServiceConnection mServiceConnection = new ServiceConnection() {

@Override

public void onServiceConnected(ComponentName componentName, IBinder iBinder) {

InterfaceC1402c c1400a;

SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.logger.mo2231d( SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.getClass().getSimpleName() + " : onServiceConnected() called with: className = [" + componentName + "], activeTargetPackageName = [" + SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.activeTargetPackageName + "]");

SamsungBindInstallAgentService samsungBindInstallAgentService = SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this;

samsungBindInstallAgentService.samsungInstallerBinder = iBinder;

int i10 = AbstractBinderC1401b.f4081c;

if (iBinder == null) {

c1400a = null;

} else {

IInterface queryLocalInterface = iBinder.queryLocalInterface("com.sec.android.app.samsungapps.api.aidl.IInstallAgentAPI");

c1400a = (queryLocalInterface == null || !(queryLocalInterface instanceof InterfaceC1402c)) ? new C1400a(iBinder) : (InterfaceC1402c) queryLocalInterface;

}

samsungBindInstallAgentService.installAgentAPI = c1400a;

SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.mBound = true;

SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.isBinding = false;

if (TextUtils.isEmpty(SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.activeTargetPackageName)) {

SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.dequeueDownloadToken();

return;

}

try {

SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.logger.mo2237i( SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.getClass().getSimpleName() + " : resume install package after reconnected = " + SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.activeTargetPackageName);

SamsungBindInstallAgentService samsungBindInstallAgentService2 = SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this;

samsungBindInstallAgentService2.startInstall( samsungBindInstallAgentService2.activeTargetPackageName);

} catch (Exception e10) {

e10.printStackTrace();

}

}

@Override

public void onServiceDisconnected(ComponentName componentName) {

SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.logger.mo2231d( SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.getClass().getSimpleName() + " : onServiceDisconnected() called with: className = [" + componentName + "]");

SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.installAgentAPI = null;

SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.mBound = false;

SamsungBindInstallAgentService.this.isBinding = false;

}

};

Realme

Some versions of AppHub reference com.applovin.oem.p036am.device.realme.RealmeDownloader, which through its name indicates that it is a Realme library to perform downloads.

According to a May 28, 2023 change analysis, RealMe added AppHub to its phones beginning in its F.07 update.

Cricket, Oppo, Orange, Sliide, Tinno

In AppHub code, I found references to Cricket, Oppo, Orange, Sliide, Tinno. But I didn’t see full installation integrations for these carriers within the AppHub versions I received. That said, it seems AppLovin provides a different AppHub APK for each partner. When I bought a device from T-Mobile, I naturally received a phone with the T-Mobile AppHub APK. The lack of other carriers’ AppHub APKs on a T-Mobile device should not be seen as a surprise.

An AppLovin press release describes a partnership with OPPO for “mobile app recommendations that “connect[] users with a wide variety of apps, from popular games to productivity tools, designed to cater to the unique preferences of each user.” This could be a euphemism for installing games when users merely view ads for those apps.

Xiaomi and TCL

The Culper report discusses AppLovin AppHub partnerships with Xiaomi and TCL. I did not find evidence of integration between AppHub and these companies in the code I reviewed. Here too, there could be other APK versions that implement these integrations.

AppLovin Execution Path: Java interceptors route the /install-app call to T-mobile’s InstallerHelper

This post is part of AppLovin Nonconsensual Installs > Execution Path. See important disclosures.

In DirectDownloadActivity, I presented code in which execution flows to DirectDownloadMainFragment C3374l2. Then C3374l2’s constructor creates C3298a3:

// DirectDownloadMainFragment

public C3374l2(C1947f c1947f, C3743e c3743e, InterfaceC3372l0 interfaceC3372l0, C1059x c1059x, C1059x c1059x2, boolean z) {

...

this.f10629x0 = c1947f;

this.f10630y0 = c3743e;

this.f10631z0 = interfaceC3372l0;

this.f10620A0 = c1059x;

this.f10621B0 = c1059x2;

this.f10622C0 = z;

this.f10623D0 = AbstractC3379m0.m5742a(interfaceC3372l0);

this.f10624E0 = AbstractC3379m0.m5743b(interfaceC3372l0);

C3367k2 c3367k2 = new C3367k2(new C0597a(4, this), 1);

InterfaceC6440g m9576c = AbstractC6434a.m9576c(EnumC6441h.f19368t, new C5289f(9, new C5289f(8, this)));

this.f10625F0 = new C5732d(AbstractC4237v.f12869a.mo6593b(C3298a3.class), new C0733o(1, m9576c), c3367k2, new C0733o(2, m9576c));

this.f10627H0 = true;

}

Next C3298a3’s constructor creates C5252f, which acts as a WebView interceptor manager:

//WebView interceptor manager

public C3298a3(Application application, C1947f c1947f, C3743e c3743e, InterfaceC3372l0 interfaceC3372l0) {

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(c1947f, "mergedConfig");

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(c3743e, "analyticsEventContext");

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(interfaceC3372l0, "appLookupKey");

C2325b c2325b = new C2325b(23);

C4863a c4863a = new C4863a(application);

C5252f c5252f = new C5252f(c4863a, c1947f, c3743e, interfaceC3372l0, AbstractC4118e.m6305K(c4863a).f12518G, c2325b);

Then C5252f registers endpoint handlers. The HTTP endpoint handler for /install-app is C5461u:

//create endpoint handlers

public C5252f(C4863a c4863a, C1947f c1947f, C3743e c3743e, InterfaceC3372l0 interfaceC3372l0, C2495r1 c2495r1, C2325b c2325b) {

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(c1947f, "mergedConfig");

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(c3743e, "analyticsEventContext");

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(interfaceC3372l0, "appLookupKey");

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(c2495r1, "directDownloadPackageManager");

C2608d1 c2608d1M4552b = AbstractC2611e1.m4552b(7);

this.f15673b = c2608d1M4552b;

this.f15674c = c2608d1M4552b;

C4281e c4281e = AbstractC1870m0.f5700a;

C3660c c3660cM382i = AbstractC0001a.m382i(c4281e, c4281e);

C4147i c4147iM6305K = AbstractC4118e.m6305K(c4863a);

PackageManager packageManager = c4863a.getPackageManager();

AbstractC4226k.m6578d(packageManager, "getPackageManager(...)");

C5247c0 c5247c0M4916q = C2866e0.m4916q("install-app", new C5461u(c4147iM6305K, c3743e, c1947f, interfaceC3372l0, packageManager, c2495r1, c4147iM6305K.f12513B, c2325b));

C5247c0 c5247c0M4916q2 = C2866e0.m4916q("cancel-install-app", new C5437h(c4147iM6305K, c3743e, c2495r1, 1));

C5247c0 c5247c0M4916q3 = C2866e0.m4916q("launch-app", new C5465y(c3743e, c4147iM6305K));

C5247c0 c5247c0M4915p = C2866e0.m4915p("install-app-state", new C5437h(c4147iM6305K, c3743e, c2495r1, 2));

C5247c0 c5247c0M4915p2 = C2866e0.m4915p("await-install-state", new C5437h(c4147iM6305K, c3743e, c2495r1, 0));

C5431e c5431e = new C5431e(c4147iM6305K, c1947f, c3743e, interfaceC3372l0, c4147iM6305K.f12513B);

AbstractC1838d0.m3857y(c3660cM382i, null, null, new C5250e(c5431e, this, null), 3);

C5247c0 c5247c0M4915p3 = C2866e0.m4915p("app-version-info", c5431e);

Map mapSingletonMap = Collections.singletonMap(C2587r.f7833d, new C5447m(c4147iM6305K, c3743e, c2325b));

AbstractC4226k.m6578d(mapSingletonMap, "singletonMap(...)");

this.f15675d = AbstractC0209q.m798M(c5247c0M4916q, c5247c0M4916q2, c5247c0M4916q3, c5247c0M4915p, c5247c0M4915p2, c5247c0M4915p3, new C5247c0("installation-on-dismiss-enabled", mapSingletonMap));

}

C5461u activates DirectDownloadPackageManager C2495r1:

//DirectDownloadPackageManager

public C5461u(C4147i c4147i, C3743e c3743e, C1947f c1947f, InterfaceC3372l0 interfaceC3372l0, PackageManager packageManager, C2495r1 c2495r1, C4120g c4120g, C2325b c2325b) {

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(c3743e, "analyticsEventContext");

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(c1947f, "mergedConfig");

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(interfaceC3372l0, "appLookupKey");

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(c2495r1, "directDownloadPackageManager");

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(c4120g, "appDetailRepository");

...

this.f16109f = packageManager;

this.f16110g = c2495r1;

...

C2495r1’s coroutine resume function m4446F() passes execution to C0033f0, which acts as a bridge to the T-Mobile InstallerHelper:

public final Object m4446F(C1947f c1947f, AbstractC1576c abstractC1576c) {

...

mo436z = ((C0033f0) c5119b2.f15215t).mo436z(c1947f, c2534z0);

Then C0033f0 creates C0023a0 (which acts as an installation executor), with execution flowing to coroutine resume function m431o():

public final Object m431o(C1947f c1947f, String str, InterfaceC6364j interfaceC6364j, int i, C6384t c6384t, EnumSet enumSet, InterfaceC0894d interfaceC0894d) {

...

C0023a0 c0023a0 = new C0023a0(c4236u, c0033f0, c1947f2, interfaceC6364j2, str2, enumSet2, null);

Finally, C0023a0 continuation entry point mo410r() activates T-Mobile InstallerHelper’s startInstall():

import com.tmobile.p432dm.cmsdk.InstallerHelper;

import com.tmobile.p432dm.cmsdk.InstallerHelperResult;

...

public final Object mo410r(Object obj) {

...

InstallerHelperResult startInstall$default;

...

startInstall$default = InstallerHelper.startInstall$default((InstallerHelper) m458a, arrayList2, str, 1, this.f520F.contains(EnumC6366k.f19171a), 0, 0, 0, null, null, null, null, null, 4080, null);

...

InstallerHelperResult.Fail fail = (InstallerHelperResult.Fail) startInstall$default;

Throwable cause = fail.getCause();

String m5237p = AbstractC2945r1.m5237p("Failed to start install: ", fail.getMessage());

Object[] objArr3 = new Object[i3];

Object[] copyOf4 = Arrays.copyOf(objArr3, objArr3.length);

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(copyOf4, "args");

C6241b c6241b3 = AbstractC6243d.f18832a;

c6241b3.m9419f("Array/".concat("Installer"));

c6241b3.mo9417d(6, cause, m5237p, Arrays.copyOf(copyOf4, copyOf4.length));

Execution continues in T-Mobile InstallerHelper performs an install.

AppLovin Execution Path: WebView loads JavaScript Resources files that check and act on auto-install

This post is part of AppLovin Nonconsensual Installs > Execution Path. See important disclosures.

The WebViewClient C4785e() constructor prepares the web view. Where a response includes references to resources in com.applovin.array.resources, or otherwise within the arrayList2 list, local resource interception substitutes resources from the APK’s Resources folder.

public C4785e(ArrayList arrayList, InterfaceC4868a interfaceC4868a, Resources resources) {

AbstractC4226k.m6579e(arrayList, "xhrRequestHandlersManagers");

this.f14379b = C5552e1.m8618a(Integer.MAX_VALUE, 6, null);

this.f14380c = AbstractC1469t3.m3132E("VISUAL_STATE_CALLBACK");

ArrayList arrayList2 = new ArrayList();

C4117d c4117d = new C4117d("https", "embedded.directdownload.arrayengine.com");

arrayList2.add(new C4870c(c4117d, interfaceC4868a));

arrayList2.add(new C5273p0(c4117d, arrayList));

arrayList2.add(new C5049c(c4117d));

arrayList2.add(new C4870c(new C4117d("com.applovin.array.resources", ""), new C4115b(resources)));

this.f14381d = arrayList2;

...

The most important local resource is app\src\main\assets\directdownload-ui\assets\index-BFfWBgBF.js, a substantial block of minified JavaScript which is 13,069 lines long after pretty-printing.

Among other tasks, this file parses a server response to create what it calls a mergedConfig which determines what settings to use for the possible installation. These settings include “IsAutoInstall”, which is set based on what is received from the server, potentially supplemented by a default value from a local data structure called wt.

function Op(e, t) { //check whether isAutoInstallEnabled

return e ? e.toLowerCase() === pr : t ? t.toLowerCase() === pr : wt.isAutoInstallEnabled

}

const ...

s = t[Ct.IsAutoInstallEnabled],

o = t[Ct.IsAutoInstallEnabledOld], ...

return {...

isAutoInstallEnabled: Op(s, o), ...

The default value is to enable AutoInstall:

const wt = { //default settings arrayPrivacyPolicyUrl: "https://www.applovin.com/array-privacy-policy/", arrayTermsOfServiceUrl: "https://www.applovin.com/array-terms/", autoInstallDelayMs: 5e3, isAutoInstallEnabled: !0, isBugsReportingEnabled: !1, isInstallingProgressEnabled: !1, isVideoSectionEnabled: !1, isVideoSectionExpanded: !1, isOneClickInstallOnEnabled: !0 };

If isAutoInstall is set to true, then the JavaScript installs the app immediately:

Wt(() => {

(async () => {

...

const R = We(Qc);

if (!(!t.viewModel.isFirstLoad || !t.viewModel.isAutoInstall || R)) {

if (t.viewModel.autoInstallDelayMs <= 0) {

c();

return

...

The JavaScript function c()proceeds with installation, passing execution to installApp():

async function c() { //run the install

...

message: "App download and install start"

...

M = await Ge.installApp(t.viewModel.packageName, t.viewModel.versionCode, t.adToken)

The installApp() function relies on a constant specifying the endpoint destination:

me = (e => (... e.InstallApp = "install-app" ...

The installApp() function calls that endpoint:

async installApp(t, r, n) { //bridge back to Java code

pe.leaveBreadcrumb({message: `Native method "${me.InstallApp}" call`});

const a = (o=this.xhrUrls)==null ? void 0 : o[me.InstallApp];

const s = await this.nativeXhrClient.makeNativeXhrRequest({

xhrUrl: a,

body: Ia({packageName: t, versionCode: r, adToken: n})

});

return this.unwrapNativeAppResponse(s.dataText, me.InstallApp);

}

The function makeNativeXhrRequest wraps the custom httpClient.makeHttpRequest which in turn wraps the standard XMLHttpRequest, which finally calls the endpoint:

async makeNativeXhrRequest(t) {

const {body: r, headers: n, httpMethod: a = nt.Post, queryParams: s, shouldStartSpan: o, spanAttributes: d, xhrUrl: f} = t;

...

return await this.httpClient.makeHttpRequest(v);

class Hh {

makeHttpRequest(t) {

...

return new Promise((o, d) => {

const f = new XMLHttpRequest;

...

f.send(s);

Installation On Close

The preceding section explores JavaScript logic under the isAutoInstall configuration, which causes an immediate installation. But adjacent JavaScript code offers two other ways installations can proceed automatically (and still without user consent despite, in these paths, an installation screen briefly presented to the user): What the code calls “Install On Close”, and installation after a brief countdown. Key lines from the JavaScript setup that considers these possibilities:

e.AutoInstallDelayMs="ui.dd.mp.install_countdown_ms" e.IsOneClickInstallOnCloseEnabledOld="ui.dd.mp.one_click_install_on_close" e.IsOneClickInstallOnCloseEnabled="ui.dd.mp.highintent_oc"

If isOneClickInstallOnCloseEnabled, the JavaScript installs the app when the user closes the ad, also using the c() function. First, JavaScript subscribes function C() to listen for events named “native-cross-button-custom-behavior”:

function A() {

Bo.setDispatchEventBehavior()

}

Wt(() => {

Bo.setChannel((...U) => Ge.setNativeCrossButtonBehavior(...U));

const M = Yp.subscribe(C),

R = wi(A, 10),

F = Ce.topOpened.subscribe(R);

return () => (M(), F()) ...

As a result, C() runs when the user taps the x button to close the screen proposing to install an app.

Then C() forms variable F to indicate whether installs on close are disabled, and variable U to indicate whether the timer is running. If either is true, tapping X simply closes the screen (via the return line in red below). (Of course if the timer is running, installation will still proceed in due course, as detailed in the next section.) But if both are false (installs on close is enabled, and timer is not running), then the code proceeds with installation. In particular, C() then logs this event as “Installation on ‘x’ button click”, and executes function c() to proceed with installation.

function C(M) {

if (!M) return;

if (We(Ce.topOpened)) return void Ce.closeTop();

const F = We(Dr).isOneClickInstallOnCloseEnabled, U = We(f).isRunning;

if (!F || !U) {

...

return

}

pe.leaveBreadcrumb({

message: 'Installation on "X" button click',

metadata: {

isOneClickInstallOnCloseEnabled: F

},

type: "manual"

}), c(), ie.reportEvent(he.UiNativeCrossButtonClick, {

isOneClickInstallOnCloseEnabled: F,

isTimerActive: U,

shouldStartAutoInstall: !0

}), Pn(100).then(() => {

Ge.closeUiOnNativeCrossButtonClick()

})

Installation via Countdown

Alternatively, the JavaScript sets up a timer called f to count down from the number of milliseconds specified in autoInstallDelayMs:

Wt(() => {

(async () => {

...

const R = We(Qc);

if (!(!t.viewModel.isFirstLoad || !t.viewModel.isAutoInstall || R)) {

if (t.viewModel.autoInstallDelayMs <= 0) {

c();

return

}

w(o) === Xe.NotInstalled && (We(Dr).isOneClickInstallOnCloseEnabled && (J(d, !0), ie.reportEvent(he.SetInstallationOnDismissEnabled, {

value: !0

}), Ge.setInstallationOnDismissEnabled(!0)), f.reset(), f.start(t.viewModel.autoInstallDelayMs))

}

})()

});

The default starting value of the timer is 5e3, i.e. 5×103=5000 milliseconds=5 seconds.

const wt = {

...

autoInstallDelayMs: 5e3, ...

The timer’s onExpire event is set to trigger installing the app, again via the c() function:

function av(e, t) {

var N;

be(t, !0);

const [r, n] = st(), a = () => ke(Nr, "$installationStateControlledStore", r), s = () => ke(f, "$timer", r);

let o = He(gt(((N = a()) == null ? void 0 : N.status) ?? null)),

d = He(!1);

const f = rv({

...

onExpire: () => {

ie.reportEvent(he.AppAutoInstallTimerEnd), c()

...

As the timer counts down, it updates an on-screen label with the number of seconds left. First, the code creates a string Ku for the label template, with a placeholder {secondsCountdown} to be replaced by the current remaining time:

Ku = "Install in {secondsCountdown}s",

Then, a reactive state accessor r binds to the timer, running every 100ms:

const [r, n] = st(), a = () => ke(Nr, "$installationStateControlledStore", r), s = () => ke(f, "$timer", r);

...

tickIntervalMs: t = 100, ...

At the tickInterval, the reactive computation z() checks the currentMs left on the timer, storing this in variable i:

const ev = 1e3;

...

let i = z(() => s().isExpired || s().isAborted || !s().isRunning ? null : Math.ceil(s().currentMs / ev));

The reactive data exposure declares property secondsCountdown to be equal to i:

secondsCountdown: w(i),

The function w() evaluates the reactive computation and returns its current value, in turn updating the UI:

function w(e) {

...

return r && (a = e, zn(a) && zl(a)), Hn && En.has(e) ? En.get(e) : e.v

Then the reactive UI updates the displayed value, running the standard JavaScript replace method to find the placeholder {secondscountdown} and substitute the current value of secondsCountdown.

let c = z(() => !t.wasAutoInstallCancelled && typeof t.secondsCountdown == "number"),

h = z(() => t.installationStatus === Xe.Downloading || t.installationStatus === Xe.Installing),

v = z(() => t.installationStatus === Xe.Installed),

_ = z(() => {

if (w(c)) return a()[V.InstallIn].replace("{secondsCountdown}", `${t.secondsCountdown}`);

The net effect is a simple countdown timer, albeit with the unusual characteristic of showing labels like “Install in 3s” (with the letter “s” denoting seconds, and with no space between the number and the units). Notably, this “Install in 3s” format exactly matches the display one user preserved in a video, and another in a screenshot.

Execution continues in Java interceptors route the /install-app call to Tmobile’s InstallerHelper.

AppLovin Execution Path: DirectDownloadActivity loads a WebView

This post is part of AppLovin Nonconsensual Installs > Execution Path. See important disclosures.

DirectDownloadActivity.onCreate() passes execution to onAppDetailsCreate():

public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

if (isPreferences()) {

onPreferencesCreate(savedInstanceState);

} else {

onAppDetailsCreate(savedInstanceState);

}

Next onAppDetailsCreate() passes execution to setupAppDetailsFragment():

private final void onAppDetailsCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

AbstractC3305b3.f10440a.m2458q("DirectDownloadActivity::onCreate", new Object[0]);

setupAppDetailsFragment();

}

Then setupAppDetailsFragment() creates the coroutine continuation class C3359j1:

private final void setupAppDetailsFragment() {

...

C1059x c1059xM2213d = C1043j.m2213d(c4147iM6305K.f12547o, "DDNotificationsPermissionsCheck", c1057vM687d0, AbstractC1499w3.m3265I(c1061z).m2211a(new C1028b0()), 8);

AbstractC4118e.m6305K(this).f12514C.getClass();

Boolean bool = Boolean.TRUE;

C1878p c1878p = new C1878p();

c1878p.m3940c0(bool);

AbstractC1838d0.m3857y(this.intentCoroutineScope, null, null, new C3338g1(c1878p, c1059xM2213d, null), 3);

AbstractC0419z0 supportFragmentManager = getSupportFragmentManager();

AbstractC4226k.m6578d(supportFragmentManager, "getSupportFragmentManager(...)");

if (findDirectDownloadMainFragment(supportFragmentManager) == null) {

AbstractC1838d0.m3857y(this.intentCoroutineScope, null, null, new C3359j1(this, c1878p, null), 3); ...

Then c3359j1 continuation entry point mo410r() passes execution to DirectDownloadMainFragment C3374l2:

public final Object mo410r(Object obj) {

...

AbstractC0419z0 supportFragmentManager = directDownloadActivity3.getSupportFragmentManager();

C0346a c0346a = new C0346a(supportFragmentManager);

c0346a.f1416q = true;

c0346a.m1138j(C3374l2.class, "com.applovin.array.directdownload.DirectDownloadActivity.TAG.DirectDownloadMainFragment");

...

C3374l2.mo1147B(), the obfuscated version of onViewCreated, launches a coroutine C3339g2:

public final void mo1147B(View view, Bundle bundle) { //WebView loader

...

super.mo1147B(view, bundle);

AbstractC1838d0.m3857y(AbstractC1150s0.m2348e(m1163h()), null, null, new C3360j2(this, null), 3);

AbstractC1838d0.m3857y(AbstractC1150s0.m2348e(m1163h()), null, null, new C3339g2(this, null), 3);

}

C3374l2’s parent class is AbstractC3404p4, so the reference to super.mo1147B() passes execution to AbstractC3404p4.mo1147B() which creates a WebView and configures its settings and permissions:

public void mo1147B(View view, Bundle bundle) throws Exception { //Fragment onViewCreated

...

AbstractC3305b3.f10440a.m2458q("DirectDownloadFragment::onViewCreated", new Object[0]);

...

WebView webView = (WebView) viewFindViewById;

WebSettings settings = webView.getSettings();

settings.setJavaScriptEnabled(true);

settings.setDomStorageEnabled(true);

settings.setDatabaseEnabled(true);

settings.setMediaPlaybackRequiresUserGesture(false);

settings.setJavaScriptCanOpenWindowsAutomatically(true);

webView.setBackgroundColor(0);

C2574e0 c2574e0 = AbstractC1743j.f5392a;

WebView.setWebContentsDebuggingEnabled(false);

mo5736N().f10643j.incrementAndGet();

mo5737O();

...

AbstractC1838d0.m3857y(AbstractC1150s0.m2348e(m1163h()), null, null, new C3390n4(this, webView, null), 3);

AbstractC1838d0.m3857y(AbstractC1150s0.m2348e(m1163h()), null, null, new C3334f4(this, webView, null), 3);

AbstractC1838d0.m3857y(AbstractC1150s0.m2348e(m1163h()), null, null, new C3376l4(this, null), 3);

}

Return to C3374l2.mo1147B() (one step above) and notice that it also creates a new C3339g2. C3339g2 in turn passes execution to C3332f2 continuation entry point mo410r() and then to C3325e2 continuation entry point mo410r():

public final Object mo410r(Object obj) {

...

AbstractC6434a.m9578e(obj);

EnumC1139n enumC1139n = EnumC1139n.f3808u;

C3374l2 c3374l2 = this.f10528x;

C3332f2 c3332f2 = new C3332f2(c3374l2, null);

this.f10527w = 1;

...

public final Object mo410r(Object obj) {

...

AbstractC6434a.m9578e(obj);

C3374l2 c3374l2 = this.f10513x;

InterfaceC2618h m4562l = AbstractC2611e1.m4562l(new C2627k(6, new C1739h(c3374l2.mo5736N().f10412w, 1)));

C3325e2 c3325e2 = new C3325e2(c3374l2, null);

this.f10512w = 1;

...

((C2638n1) interfaceC2664x0).m4576l(obj);

...

Then C3325e2 continuation entry point mo410(r) calls coroutine continuation orchestrator m5734P to load the WebView:

public final Object mo410r(Object obj) {

...

obj = C3374l2.m5734P(c3374l2, c1059xM2213d, c0857r, this);

m5734P calls m5748L to get the URL to be loaded into the WebView.

public static final Comparable m5734P(C3374l2 c3374l2, C1059x c1059x, C0857r c0857r, AbstractC1576c abstractC1576c) {

...

objM5738Q = c3374l2.m5738Q(c0857r, c1059x, c3297a2);

return c3374l2.m5748L((C3447v5) objM5738Q);

...

public final Uri m5748L(C3447v5 c3447v5) { //Create URI with configuration

Uri.Builder buildUpon = C4785e.f14377e.buildUpon();

byte[] bytes = c6488c.m9632c(C3447v5.Companion.serializer(), c3447v5).getBytes(C0929a.f3221a);

String encodeToString = Base64.encodeToString(bytes, 11);

Uri build = buildUpon.fragment(encodeToString).build();

return build;

}

Return to AbstractC3404p4.mo1147B(), two steps above. Notice that it also creates C3334f4, whose continuation entry point mo410(r) passes execution to C3320d4:

public final Object mo410r(Object obj) {

...

C3320d4 c3320d4 = new C3320d4(abstractC3404p4, c4236u, this.f10508y, null);

Then C3320d4 continuation entry point mo410r() loads the specified URL into the WebView

public final Object mo410r(Object obj) { //WebView loader - actually loads the WebView

WebView webView;

Uri uri;

EnumC1084a enumC1084a = EnumC1084a.f3658a;

int i = this.f10487x;

WebView webView2 = this.f10485B;

AbstractC3404p4 abstractC3404p4 = this.f10489z;

if (i == 0) {

AbstractC6434a.m9578e(obj);

Uri uri2 = (Uri) this.f10488y;

C1057v c1057vM687d0 = AbstractC0192d0.m687d0(abstractC3404p4.f10704p0);

C1036f0 c1036f0 = C1036f0.f3471c;

C1059x c1059xM2213d = C1043j.m2213d(AbstractC4118e.m6295A(abstractC3404p4).f12547o, "DDWebViewPageLoad", c1057vM687d0, AbstractC1499w3.m3259C().m2211a(new C1030c0(abstractC3404p4.f10708t0)), 8);

C4236u c4236u = this.f10484A;

InterfaceC1843e1 interfaceC1843e1 = (InterfaceC1843e1) c4236u.f12868a;

if (interfaceC1843e1 != null) {

interfaceC1843e1.mo3869d(null);

}

c4236u.f12868a = AbstractC1838d0.m3857y(AbstractC1150s0.m2348e(abstractC3404p4.m1163h()), null, null, new C3397o4(abstractC3404p4, c1059xM2213d, null), 3);

C1854h0 c1854h0 = abstractC3404p4.mo5736N().f10646m;

this.f10488y = uri2;

this.f10486w = webView2;

this.f10487x = 1;

Object objM3951z = c1854h0.m3951z(this);

if (objM3951z == enumC1084a) {

return enumC1084a;

}

webView = webView2;

obj = objM3951z;

uri = uri2;

} else {

if (i != 1) {

throw new IllegalStateException("call to 'resume' before 'invoke' with coroutine");

}

webView = this.f10486w;

uri = (Uri) this.f10488y;

AbstractC6434a.m9578e(obj);

}

webView.setWebViewClient((WebViewClient) obj);

webView2.loadUrl(uri.toString());

abstractC3404p4.mo5736N().f10649p = true;

AbstractC3305b3.f10440a.m2458q("WebView::loadUrl", new Object[0]);

return C6458y.f19392a;

Execution continues in WebView loads JavaScript Resources files that check and act on auto-install